Colourism is defined as a form of prejudice and discrimination revolving around the colour of one’s skin. Not to be confused with racism, colourism occurs both between and within individual ethnicities. It’s especially prevalent in Sri Lanka and is a coalescence between classist prejudices, impacts of colonial rule and underrepresentation in current media.

It is a prominent issue in modern day Sri Lanka and affects us daily whether in the form of popular skin lightening treatments or the more pervasive snide remarks from our extended family.

As in most parts of the world, light skin was prized in pre-colonial Sri Lanka implying that one wasn’t a labourer who worked long hours in the sun and instead could afford to live comfortably in the shade. Colourism’s colonial roots date back to the 16th century as a product of the Portuguese invasion.

Simply put, light-skinned Sri Lankans were preferred over their darker-skinned counterparts by colonial invaders. Colonial rule only served to reinforce already existing prejudices and over the next 500 years, as rule passed over to the Dutch and then the British, colourism became deeply ingrained in Sri Lankan culture.

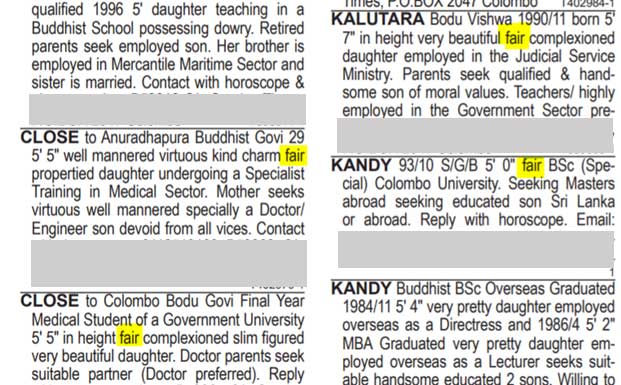

One look at the billboards and advertisements show the extent of colourism in the country. Models are selected primarily for their light skin tone and dark skin is a rarity even though most Sri Lankans have dark brown skin.

This disproportionality constructs one of the most harmful effects of colourism because it promotes the idea that dark skin is not beautiful and that it’s not worth being displayed on ads, acknowledged or associated with. The situation is exacerbated through the promotion of skin lightening procedures in the country. It’s a multibillion dollar industry across Asia – an example being the former Fair & Lovely, which is now known as Glow & Lovely.

Furthermore, comments on skin tone and the bias towards light skin have been normalised in regular conversation. It’s socially acceptable for unfamiliar aunties to despair over your ever-darkening complexion and provide unsolicited advice. This is a particularly insidious form of colourism as it’s far more personal and internal.

Most Sri Lankans grow up around such words and ideas, and are shaped by them. For many, it is natural that light skin is coveted and considered a requirement of life. This normalisation is especially problematic as it makes it more difficult to combat both subtle and obvious colourism. And it further strengthens the perceived inferiority of dark skin and that a woman with dark tones isn’t beautiful.

So how do we combat this? We must campaign for mainstream media to represent skin tones that are both dark and light, and normalise dark skin being considered attractive in society beyond basic tokenism. The fact that ‘fair’ does not equal ‘lovely’ and that light-skinned does not equal goodness (as lightening treatments would have us believe) should be communicated to people.

And the most effective method of approach is the one most available to us –simply using our voices to speak out. Although it can be hard, speaking out against colourist views that impact us daily is imperative if we want to spark change.

This does not mean that nothing has been done yet. Only recently in 2020, we saw the resurgence of the 2016 #unfairandlovely movement in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests. Represented by two Sri Lankan sisters in Texas, #unfairandlovely sought to embrace the beauty of dark skin and discard colourist restrictions.

Slowly but surely, colourism is being called out by people such as model Jeenu Mahadevan and businesswoman/model Kalpanee Gunawardana, who are addressing prejudice in the fashion industry. The fact that I am writing this article and that you are reading it is one more step in the right direction.

Perhaps the next time you meet your extended family and hear an offhand remark, you might explain the effects and problematic history of colourism. Or you can tell a dark-skinned nangi thatyou think she is beautiful.

This article has been republished from The Moir Post, Issue 7 (March 2021).

Leave a Reply

View Comments